1) His Biography:

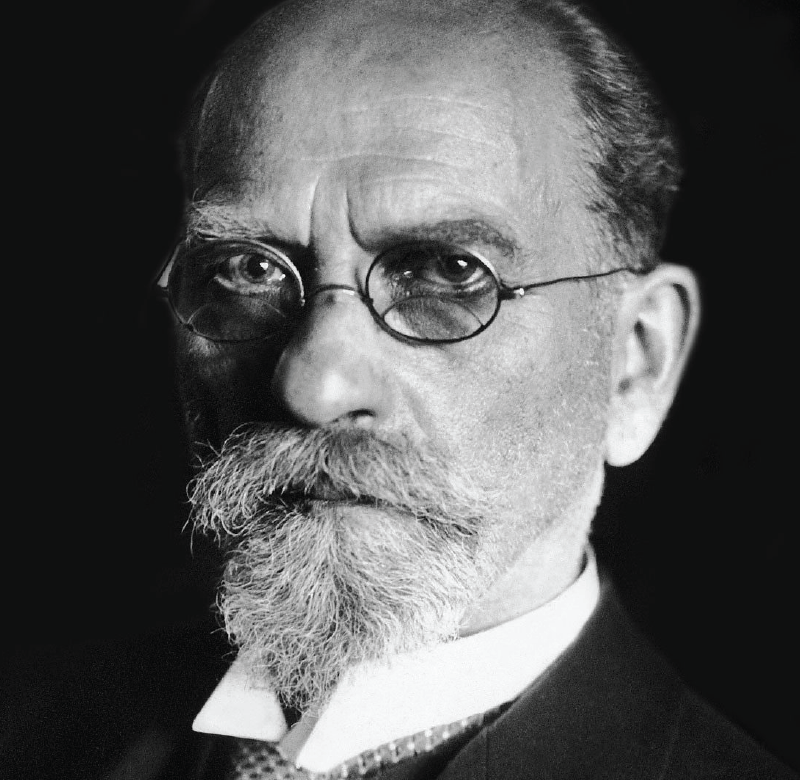

The founder of the field of phenomenology and one of the most influential thinkers of the 0th century, Edmund Husserl was born as Edmund Gustav Albrecht Husserl on April 8, 1859, in Prossnitz, Moravia. He is credited with making significant contributions to the fields of philosophy, linguistics, sociology, and cognitive psychology. The orthodox Jewish family that Edmund came from moved frequently throughout his boyhood.

He started his traditional German education at Vienna’s Realgymnasium when he was 10 years old. Later, for his secondary education, he was sent to the Staatsgymnasium in Olmutz. Edmund enrolled in the University of Leipzig, where he studied mathematics, physics, philosophy, as well as a number of astronomy and optics courses. After doing a doctoral dissertation on the calculus of variations, he was awarded his Ph.D. in 1883.

Husserl accepted a teaching position in Berlin to start his professional career, but in 1884 he was compelled to return to Vienna because of his intense interest in Franz Brentano’s ideas. Husserl was greatly influenced by Franz Brentano’s lectures, especially his concept of intent, which motivated him to pursue a career in philosophy and psychology.

Edmund moved to Halle in 1886 and spent the following year immersing himself in psychological study. His Habilitationsschrift, titled “The Philosophy of Arithmetic,” was written. He became a Christian during this time and married Malvine Charlotte Steinschneider, with whom he had three children. In his spare time, Husserl wrote some of his most important works on phenomenology, including “Logische Untersuchungen,” which serves as an introduction to the field of phenomenology. Husserl was appointed as the Privatdozent of Halle.

Husserl started his 16-year stint at the University of Gottingen in 1901, and it was during this time that he developed his many theories on phenomenology, establishing it as a distinct field dedicated to describing events and things without the need of metaphysical or theoretical hypotheses. Numerous students started enrolling in his courses. Ideas: A General Introduction to Pure Phenomenology, a widely praised and ground-breaking discourse he published in 1913, serves as an introduction to his theory of phenomenological reduction, which offers perceptual tools for the contemplation and reflection of objects while conducting observations.

Husserl said that the phenomenological reduction approach helps to eliminate the prejudices associated with reality and makes it easier for the researcher to concentrate on the “bracketing of existence.” Husserl undertook a number of experiments to understand the mental mechanisms behind perception and cognition, and he came to the conclusion that the existence of an object to be contemplated is a prerequisite for consciousness.

As World War I broke out, Husserl’s academic career was disrupted in a number of ways. He started losing the majority of his pupils to the conflict, and tragedy hit his family in 1916 when his son was killed while fighting on the front lines. Edmund was saddened and abandoned his professional life for a whole year as he grieved. However, he was hired as a professor at Freiburg in Beisgau in the fall of 1916. During this time, he wrote a number of highly regarded books, some of which were released after his passing. Among these is “Cartesian Meditations,” in which Husserl discusses the impact that individual consciousness has on philosophy, history, and society.

Up to his death in 1938 from pleurisy, Edmund Husserl taught in Freiburg. His most wellknown works include “Phenomenology of Inner Time-Consciousness,” “Formal and Transcendental Logic,” and “Experience and Judgment.” He has made a number of highly original creative contributions to the academic world.

2) Main Works:

Philosophy of Arithmetic:

The fundamental concern of the book is a philosophical examination of the notion of number, which is the most fundamental idea on which the entirety of mathematics and arithmetic can be built. Husserl, following Brentano and Stumpf, uses psychological techniques to search for the “origin and content” of the concept of number in order to move this analysis along.

Logical Investigations:

Husserl claims in Volume I that the difficulties he ran into when trying to produce a “philosophical clarification of pure mathematics” made him aware of the limitations of logic as it was then understood. Husserl progressed from studying mathematics to developing “logical researches into formal arithmetic and the theory of manifolds” He admits that he had once believed that psychology provided logic with “philosophical clarification,” and he explains why he later changed his mind.

Logic “seeks to search into what pertains to genuine, valid science as such, what constitutes the Idea of Science, so as to be able to use the latter to measure the empirically given sciences as to their agreement with their Idea, the degree to which they approach it, and where they offend against it”, according to Husserl.

Husserl opposes empiricism and psychologism, a theory on the nature of logic that holds that “the underlying theoretical foundations of logic lay in psychology.” He uses John Stuart Mill as an example of psychologism in his critique of Mill’s logic. Immanuel Kant’s ideas, as presented in the Critique of Pure Reason (1781), as well as those of other philosophers including Franz Brentano, Alexius Meinong, and Wilhelm Wundt, are also discussed. In Volume II, Husserl continues to criticise Mill and analyses the application of linguistic analysis to logic.

Cartesian Meditations:

The key components of Husserl’s mature transcendental phenomenology are introduced in the text. These components include—but are not limited to—the transcendental reduction, the epoch., static and genetic phenomenology, eidetic reduction, and eidetic phenomenology. Husserl contends in The Fourth Meditation that transcendental idealism is nothing more than transcendental phenomenology.

The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology:

Part I of the work is titled “The Crisis of the Sciences as Expression of the Radical Life-Crisis of European Humanity,” Part II “Clarification of the Origin of the Modern Opposition between Physicalistic Objectivism and Transcendental Subjectivism”, and Part III “The Clarification of the Transcendental Problem and the Related Function of Psychology”. Husserl examines what he views as a scientific crisis in Part I, while introducing the idea of the lifeworld and talking about the scientist Galileo Galilei in Part II.

3) His contribution to philosophy:

Husserl established his own distinctive way of working; he wrote down every idea that came to him, and over the course of his life, he produced more than 40,000 pages. Husserl wrote “.ber den Begriff der Zahl” (“On the concept of Number”) in 1887 under the guidance of Carl Stumpf (1848–1936), a former pupil of Franz Brentano (1838– 1917), which would serve as the foundation for his first significant work, the “Philosophie der Arithmetik” (“Philosophy of Arithmetic”) of 1891. With the primary objective of giving mathematics a solid foundation, he attempted to merge mathematics, psychology, and philosophy in these early works.

During his time at the University of Gottingen, he published two of his most important philosophical works: the first volume of “Ideen zu einer reinen Phenomenologie und phenomenologischen Philosophie” (“Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and to a Phenomenological Philosophy”), published in 1913, and the “Logische Untersuchungen” (“Logical Investigations”), published in 1901 after a thorough study of the British Husserl himself thought that his work constituted the completion of all of philosophy from Plato on since, in his view, he had established a description of reality that could not be refuted. He introduced the fundamental topics of his theory of Phenomenology in these works, particularly in the “Ideen.”

Husserl began from the premise that, for each of us, there is only one object that is indubitably certain, namely our own conscious awareness, much like Descartes, more than two centuries ago. He came to the conclusion that this must be the starting point for expanding our understanding of the environment. However, we cannot differentiate between states of consciousness and objects of consciousness based solely on experience. Our awareness and consciousness must be awareness and consciousness of something.

Husserl concurred with sceptics throughout history who claimed that we can never know whether objects of consciousness have an independent existence apart from us, but he insisted that they do indisputably exist as objects of consciousness for us and can therefore be investigated as such without making any erroneous assumptions about their independent existence. Husserl’s overarching concept served as the foundation for the influential Phenomenology school of philosophy.

What he dubbed “phenomenological reduction,” which is simply a form of meditation on intellectual substance, was his fundamental methodological tenet. He claimed that by suspending all preconceptions about it, including (and especially) those derived from what he called the “naturalistic stance,” he may properly “bracket” the data of awareness. Therefore, in his thought, it truly made no difference whether an object was being discussed actually existed or not as long as he could at least think of it, and objects of pure imagination could be evaluated with the same seriousness as information derived from the objective world.

Husserl came to the conclusion that consciousness does not exist independently of the phenomena or things it considers. Following Brentano, he referred to this trait as “intentionality” (or “object-directedness”), and it represented the notion that the only entity in the entire universe that is capable of directing itself toward other things outside of itself is the human mind. Husserl spoke of the idea of intentional content, which he defined as something that exists in the mind that functions somewhat like a built-in mental description of external reality and that enables us to notice and remember features of objects in the physical world.

Husserl spent his entire life honing his Phenomenology. His final three significant works were “Meditations cartesiennes” (Cartesian Meditations), published in 1931, “Formale und transzendentale Logik” (“Formal and Transcendental Logic”) published in 1929, and “Vorlesungen zur Phenomenologie des inneren Zeitbewusstseins,” (“Lectures on the Phenomenology of Inner Time-Consciousness”). After his passing in 1952, two additional volumes of his “Ideen,” which he had written while studying at Freiburg im Breisgau, were released.

Husserl claimed that mental and spiritual reality had their own reality independent of any. physical base, a position he had initially tried to avoid or overcome. However, in his later work, Husserl progressed further in that direction. He first advocated a form of transcendentalism, akin to that of Kant and the German Idealists, which claimed that our experience of things is about how they appear to us (representations), rather than how they are in and of themselves. However, his position generally fell short of claiming that there is no objective world outside of ourselves. He eventually reached an even more radical Idealist perspective, which effectively denied that external objects existed at all outside of human mind, as he continued to steadily develop his ideas.

4) Brentano and Husserl:

Although Brentano is a highly prominent philosopher in his own right and a teacher of many distinguished philosophers, he is most recognised for having been the mentor to Edmund Husserl, the creator of phenomenology. Husserl earned his doctorate in mathematics in 1882, but in 1884, under the influence of Thomas Masaryk, he changed his field of study to philosophy and enrolled in Brentano’s Vienna lectures.

He did so up until 1886, when Brentano introduced Husserl to Carl Stumpf in Halle, where Husserl would the next year join the staff, as a serious student of philosophy. However, Husserl shifted his philosophical perspective during the 1890s before eventually “breaking through” to phenomenology with the Logical Investigations in 1900/1901. In later years, Husserl continued to distance himself from Brentanian philosophy despite his numerous admissions of Brentano’s deep effect on him; in contrast, Brentano himself was quite appalled by Husserl’s advances.

5) Freud and Husserl:

Unconscious phenomena, like fish swimming at the bottom of a vast lake, are actual aspects of consciousness, according to one particularly tenacious Freudian theory. However, since these phenomena cannot be detected, it is claimed that the basic concept of the unconscious is flawed.

In a nutshell, according to Freud, the unconscious is not a “part” of consciousness but rather a separate entity that can only be introduced from within a clinical setting. It is not a component of either a scientific-psychological examination nor of the “natural attitude” in the phenomenological sense. Freud asserts that the unconscious is a hypothesis in writings from throughout his career; it is something that is presupposed to be able to give an account of mental existence without having to accept otherwise unexplainable gaps.

However, if the unconscious has been repeatedly demonstrated to exist, it can’t possibly be a matter of thinking of the unconscious as a hypothesis. By advocating for both of these positions, Freud places himself in an uncomfortable situation, as Laplanche & Pontalis (and MacIntyre before them) have noted. Many fallacies about the ontological “realism” of the unconscious are the result of failing to confront this shift in modality, from hypothetical existence to reality.

The unconscious must be connected to the phenomenological notion of intentionality, whereby the psychoanalytical technique is understood as operating a kind of suspension of the world, an epoch. of sorts, in order to recognise that it is not only Freud’s careless crossing of boundaries.

Husserl contends that any practising psychologist performs such a partial epoch., and even though psychoanalysis is not a psychology in the conventional sense, this also true for the psychoanalyst in both the lectures on phenomenological psychology and Krisis. This view highlights the fundamental contrast that Freud himself made between all psychoanalytical thematizations of subjectivity and all other thematizations of subjectivity (which include everyday reflection, philosophy, the sciences of psychology, psychiatry, biology etc.).

From a broader viewpoint, Husserl and Freud’s contributions must be viewed in light of what they both saw as a serious crisis in the sciences. It’s interesting to note that they both believed psychology, understood broadly, to be the cause of this catastrophe. Husserl claimed that the crisis in the European sciences is primarily a problem in contemporary psychology, and that psychology’s role is therefore crucial to the resolution of this crisis or at the very least, to attempts to mitigate its effects.

From a transcendental phenomenological perspective, it is clear why psychology is being singled out: if the crisis is that the natural sciences have lost touch with their roots in subjective life and have wrapped the world in a “garb of ideas” derived from the Euclidean-Galilean mathematization of the world, then what is required is a return to their roots in the life-world and even further back to the subjective activities where the life-world is constituted.

By contesting the idea that their subjects were something that had already been decided, previous to their individual inquiries, Husserl and Freud both set about reforming the very foundations of their respective fields. In that sense, though with different lenses, they both contributed to the struggle against the dominant viewpoint of the time. Freud was more naive than most when he thought that the natural sciences would eventually include psychoanalytical thinking. Since psychoanalysis and natural-science psychology are devoted to quite distinct subjects, Husserl would have argued that this faith in the power of reason never paid off in terms of acceptance by the scientific community.

However, Freud was trying to push science’s boundaries by getting it to embrace psychoanalysis’s discoveries, but in the end, his definition of reason was too limited and too reliant on scientific prejudice. He failed to realise that the unwavering adherence to the natural scientific notion of rationality required systematic exclusion of the key results, which were centred on subjective lived experience and meaning rather than on things subject to rigorously causal explanations.

Husserl, on the other hand, got right to the point by realising that the first thing that needs to be fixed is rationality itself. In his later writings, this restoration is produced by a meticulous reconsideration of the history of philosophy rather than a search for a theory of rationality from an earlier historical period.

6) His influence in our times:

The student Husserl chose to succeed him at Freiburg is the most well-known of his pupils; Martin Heidegger. Being and Time, Heidegger’s masterpiece, was written with Husserl in mind. At the University of Freiburg, they collaborated and exchanged ideas for more than ten years; from 1920 to 1923, Heidegger served as Husserl’s assistant. Heidegger’s early work was influenced by his master, but with time he started to get fresh, original insights.

Husserl sharply criticised Heidegger in lectures he gave in 1931 as his critique of Heidegger’s work increased, particularly in 1929. Husserl was of Jewish descent, and Heidegger was notably a Nazi supporter at the time of the Nazis’ rise to power in 1933. Despite acknowledging his debt to Husserl, Heidegger continued to hold a political position that was hurtful to Husserl and disrespectful to him. There is significant scholarly discussion o Husserl and Heidegger.

While writing her doctoral thesis, The Empathy Problem as it Developed Historical and Considered Phenomenologically(1916), Edith Stein was Husserl’s student at Gottingen and Freiburg . In 1916–18, she then worked as his assistant in Freiburg. Later, she modified her phenomenology to fit the modern Thomistic school. In 1923, Ludwig Landgrebe took over as Husserl’s assistant. He worked with Eugen Fink at the Husserl-Archives in Leuven beginning in 1939. He took over as director of the Husserl-Archives in 1954. In addition to being one of Husserl’s closest friends, Landgrebe is renowned for his unique perspectives on history, religion, and politics from the perspectives of existentialist philosophy and metaphysics.

Husserl and Eugen Fink were close friends in the 1920s and 1930s. The Sixth Cartesian Meditation, which he wrote, was considered by Husserl to be the most accurate representation and continuation of his own work. Husserl’s eulogy was delivered by Fink in 1938. Husserl communicated with Roman Ingarden, one of his early Freiburg students, until the middle of the 1930s. However, Ingarden rejected Husserl’s later transcendental idealism because he believed it would lead to relativism. German and Polish are the two languages that Ingarden wrote in. He developed his own realistic perspective in his Spor o istnienie świata (German: Der Streit um die Existenz der Welt; English: “Dispute about the Existence of the World”), which also assisted in the dissemination of phenomenology in Poland.

At 1901, Max Scheler and Husserl met in Halle, and Husserl’s phenomenology became a methodological turning point for Scheler’s own philosophy. One of the first few editors of the journal Jahrbuch für Philosophie und Phenomenologische Forschung was Scheler, who was at Gottingen when Husserl lectured there (1913).

The new journal published two of Scheler’s works, Formalism in Ethics and Nonformal Ethics of Value, in 1913 and 1916, respectively. But as a result of Scheler’s legal issues, the two men’s personal connection grew strained, and Scheler eventually left for Munich. Scheler claims that Husserl was “seriously indebted” to him throughout his career, despite the fact that he eventually criticised Husserl’s idealistic logical methodology and suggested a “phenomenology of love” in its place.

In 1929, Emmanuel Levinas delivered a speech at one of Husserl’s final seminars in Freiburg. He also published a lengthy review of Husserl’s Ideen (1913) in a French journal that same year. Husserl’s Meditations cartesiennes(1931) was translated into French by Levinas and Gabrielle Peiffer . Heidegger first impressed him, and he started writing a book about him.

However, when Heidegger joined the Nazis, he abandoned the idea. He wrote about Jewish spirituality after the holocaust; the Nazis having murdered the majority of his family in Lithuania. Then Levinas started to produce pieces that would be well-known and admired. Max Weber’s interpretive sociology is rigorously grounded in Husserl’s phenomenology in Alfred Schutz’s Phenomenology of the Social World. This work impressed Husserl, who asked Schutz to collaborate with him. Despite eventually coming to disagree with certain of Husserl’s analyses, Jean-Paul Sartre was also greatly inspired by him. Sartre adopted Heidegger’s ontology and rejected Husserl’s transcendental interpretations introduced in Ideen (1913).

Edmund Husserl’s work on perception, intersubjectivity, intentionality, space, and temporality, especially Husserl’s notion of retention and protention, had an impact on Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception. For instance, Merleau-Ponty’s explanation of “motor intentionality” and sexuality preserves the crucial framework of Ideen I’s noetic/noematic correlation while further concretizing what Husserl meant by awareness particularising itself into modes of intuition.

“The Philosopher and His Shadow” is maybe Merleau-Ponty’s most overtly Husserlian piece. Depending on how one interprets Husserl’s descriptions of eidetic intuition, which are presented in Husserl’s Phenomenological Psychology and Experience and Judgment, Merleau-Ponty may not have agreed with the notion of “eidetic reduction” or the purportedly produced “pure essence.” The first person to study at the Husserl-archives in Leuven was Merleau-Ponty.

Due to Sartre, Gabriel Marcel officially repudiated phenomenology, which has a large following among French Catholics, but did not do the same for existentialism. He was fond of Husserl, Scheler, and (albeit cautiously) Heidegger. His use of phrases like “ontology of sensability” when referring to the body shows that phenomenological philosophy has had an influence. It is well known that Kurt Godel read Cartesian Meditations. Husserl’s work received a lot of praise from him, particularly in regards to “bracketing” or “epoch..”

Husserl appears to have influenced Hermann Weyl’s interest in intuitionistic logic and impredicativity. Through his wife Helene Joseph, who studied under Husserl in Gottingen, he was introduced to Husserl’s writings. Husserl’s theories were heavily incorporated into Colin Wilson’s “New Existentialism,” especially with relation to his “intentionality of consciousness,” which is mentioned in several of his publications. In addition to using Husserl’s concept of vital insight in his book Der Raum, Rudolf Carnap was also influenced by Husserl. His concept of “formation rules” and “transformation rules” is based on Husserl’s logic.

In 1950, Hans Blumenberg was awarded his habilitation for a dissertation on ontological distance that examined the phenomenological crisis in Husserl’s work. Despite their differences, Roger Scruton used Husserl’s ideas in Sexual Desire (1986). Beyond the bounds of the European and North American legacies, the Husserlian phenomenological tradition continues to have an impact in the twenty-first century. It has already begun to have an influence (indirectly) on research on Eastern and Oriental thought, including studies on the origins of philosophical thought in the development of Islamic concepts.